Paint Stronger Landscapes With This 5-Step Process

When you look at an artist’s finished painting, you notice the color, the atmosphere, the light.

But what makes all of that possible is something you cannot see: their painting process. These are the steps an artist works through to build a finished piece.

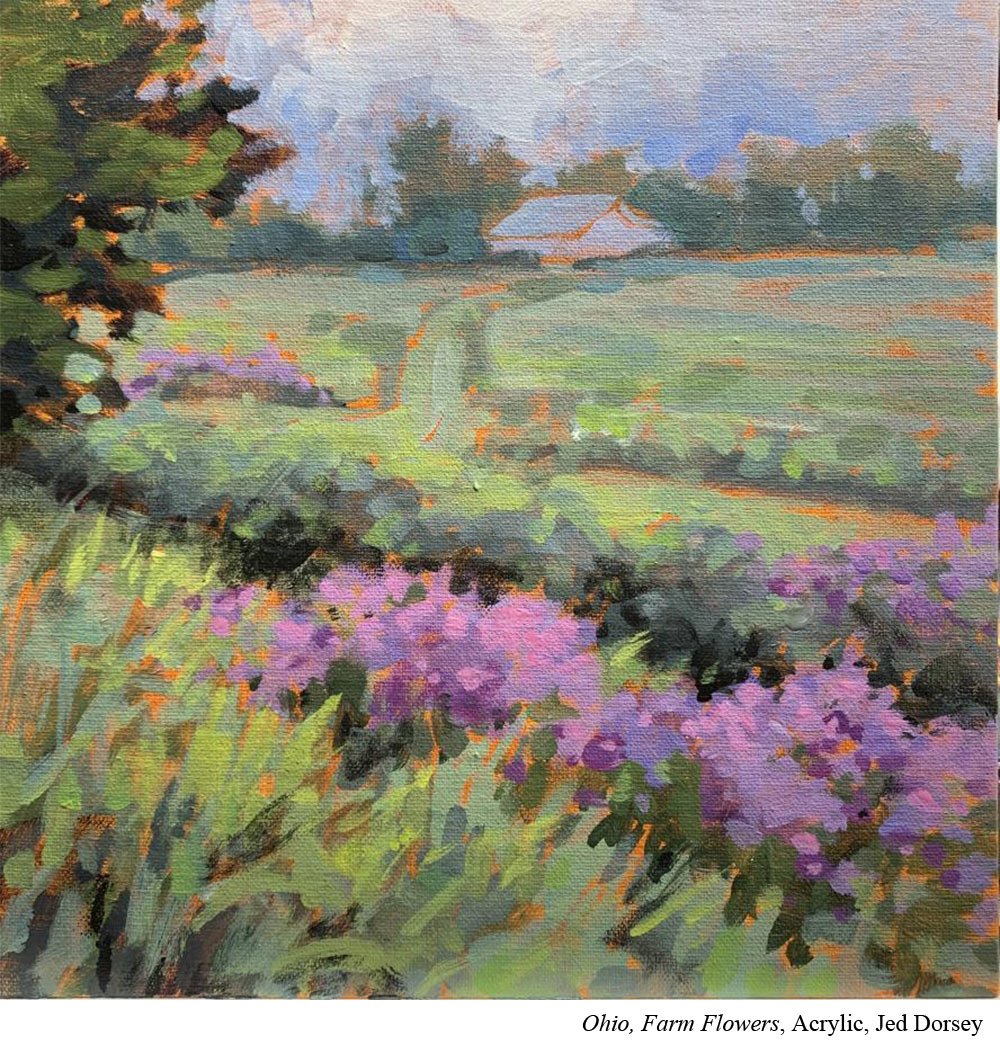

Jed Dorsey (Ep.27) has a process he returns to again and again to build his work. These steps don’t guarantee that every painting will be a success. But it does lower overwhelm and confusion.

You may already move through these steps instinctively. But naming them changes how you paint.

When you think in stages, you can evaluate in stages. You do not have to solve everything at once. You focus on one phase at a time.

At the end of each stage, you pause and ask not just, “How’s it looking?” but “Did I accomplish what this stage required?”

Dorsey’s five steps are:

Design

Draw

Block In

Refine

Finish

Let’s walk through them.

“At the end of each stage you can think, ‘Well, how's it looking?’ ”

-Jed Dorsey

Step 1: DESIGN

Design happens before you ever pick up your brush.

This might mean:

Creating thumbnail sketches

Cropping your reference photo

Testing multiple compositions

Adjusting value groupings

In Dorsey’s opinion, this is the most important stage of the entire painting.

You can have beautiful brushwork and gorgeous color. But if your design is weak, the painting will feel mediocre.

On the other hand, if the design is strong, even average brushwork can still produce a compelling painting.

Thumbnail sketches are powerful because they are fast. Five to ten minutes. Several variations. Low commitment. High payoff.

If you skip this stage, you may paint for hours only to reach the end and wonder:

“Why doesn’t this work?”

And by then, redesigning is painful.

It is far easier to adjust your composition in a two-inch sketch than on a finished canvas.

STEP 2: DRAW

In the draw stage, you transfer your design onto the canvas.

One critical consideration here is aspect ratio.

If your design is long and horizontal but your canvas is square, something has to give. When artists ignore this mismatch, elements get compressed or stretched. The painting feels off, but they cannot quite explain why.

Dorsey encourages students to ask:

“Am I painting for a particular canvas?”

If yes, your design must match that format. Either adjust the reference or choose a canvas that supports your composition.

This stage is about placement, proportion, and structure. You are building the scaffolding.

“So I am always thinking about that and I try to get students to ask, “Am I painting for a particular canvas?” And if yes, you want to just make sure your design matches that.”

- Jed Dorsey

STEP 3: BLOCK IN

Blocking in means covering the canvas with color and value.

Dorsey typically starts with the darks. Thin, transparent layers underneath. Then midtones. Then lights. The thickest and most opaque paint goes on top.

This thin-to-thick principle is especially important in oils, but it still creates a pleasing visual structure in acrylic.

The deeper reason blocking in matters is this:

You cannot accurately judge color or value in isolation.

A color placed on white canvas may look too dark. The same color on a dark canvas may look too light. It is only when the entire painting is covered that you can properly evaluate relationships.

If you fully finish your focal point before blocking in the rest, you risk having to redo it once the surrounding colors shift.

The block in stage is important for what it is and for what it isn’t.

It isn’t about perfection. It’s isn’t about form or details.

It’s about covering your canvas so you can start thinking about value and color relationships.

Then move on.

STEP 4: REFINE

This is the longest stage.

The block-in was about big, simple value shapes.

Refining is where you begin creating the illusion of three dimensions and depth.

You adjust edges. You soften transitions. You clarify focal points.

Dorsey warns that this stage can be mentally exhausting. If he reaches a point where he does not know what to do next, that is his cue to step away. Continuing to paint without intention rarely improves a piece.

Painting just makes you tired. You stop seeing the painting clearly. So your solution here is to take a break. In fact, Dorsey very intentionally steps away. Sometimes overnight. He knows there are things he can’t see at the end of a long painting session that will be much clearer come morning.

“So the other important thing with blocking in your painting is that it makes it easier to evaluate everything.” - Jed Dorsey

Step 5: FINISH

When you return with fresh eyes, one of two things happens:

You look at the painting and think, “It’s done.”

Or you instantly see what needs adjustment. A distracting line. A dark shape that pulls attention. A highlight that needs to be softened.

Because Dorsey prefers looser, impressionistic style he often saves a few bold brushstrokes for the end. He wants to finish with the same energy he started with.

Enthusiasm at the beginning.

Enthusiasm at the end.

Put It to Practice

For your next painting, audition Dorsey’s 5 stages. Work to use them as distinctive steps… not something you rush through without stopping.

Before you paint, set a timer for 10 minutes and create at least three thumbnail sketches. Do not skip this. Choose the strongest design before you ever touch your canvas.

When you move to the canvas, pause and ask:

Does my design match this aspect ratio?

If it doesn’t, change your canvas so that it does. (Or redo your thumbnails to match the canvas you have.)

“You want to finish your painting with enthusiasm... just like you start a painting.”

- Jed Dorsey

During the block-in stage, avoid the urge to start working on details. The goal here is to cover the entire canvas first. Focus only on big shapes and value relationships. Think simple. Think two-dimensional.

When refining, notice your energy. Are you still making intentional adjustments, or are you just fussing? If you cannot clearly name what needs to change, that is your signal to put the brush down and take a break.

Finally, build in a break near the end. Do this even if you’re still feeling high energy painting. Your break might mean taking a walk. It might mean sleeping on it. Come back with fresh eyes and make only the changes that are obvious and purposeful.

After the painting is complete, as yourself:

Which stage felt strongest for you?

Which stage felt rushed or uncomfortable?

That answer tells you exactly where to focus your next round of practice.

Get articles like this and new podcast episodes sent straight to your inbox by signing up for the newsletter below.