The Importance of Drawing: An Interview with Mark Eanes

Mark Eanes has been on the show twice, first to talk about Color (Ep.11) and then Design & Composition (Ep.28.) Today he’s back for a written interview to discuss the importance and power of drawing, both as a tool for painting but also as a pursuit in and of itself.

Learn more about his course Language of Drawing at MarkEanesAcademy.com.

You've taught painting for several decades. Is drawing just for painters hoping to be photo realists or is drawing important for artists interested in any style or subject? Why?

Let me set the stage here…Vincent Van Gogh remarked that drawing was the backbone of painting. Ingres stated that drawing was the probity of art, referring to honesty and integrity. Those are noble statements, to be sure, but were uttered well before abstraction in art. So, is drawing worthwhile or necessary for all artists? Absolutely not. Not in this day and age.

Instead, drawing is a worthy endeavor and discipline for those artists who have an interest in observing the world in all its complexity, and to record those observations, either directly from observation or from memory and imagination. It matters not whether they (the artists or the drawings themselves) are representational or non-representational. What matters is a desire to explore a rich and deeply satisfying mode of personal expression that is immediate, true and honest.

For representational painters, how does drawing help throughout a painter's process?

When it comes to observation, here is one way I explain the usefulness of drawing to my artists and students:

Imagine I put before you an old shoe with lots of character and ask you to draw it once, and once only. Next, I remove the shoe. I then ask you to draw that same shoe from different angles and points of view from your memory and imagination. You would be hard pressed to do so.

“Drawing has given me the gift of inquisitiveness. It has provided me with the ability to look at things with wonder and curiosity, to engage my imagination and at times to be in awe of what I am seeing and experiencing.”

- Mark Eanes

Now imagine you were to draw that same shoe many times, from brief sketches to longer studies, from many points of view. If I were to remove the shoe, you would know it intimately and would have little difficulty seeing it in your mind’s eye and creating drawings worthy of your memory and imagination .

One more example:

Years ago I had a student, an older woman who had come back to drawing after many years. I gave the class the assignment to draw a challenging form of nature using a technique known as cross-contour, and to spend at least one hour or more to create a sustained drawing.

The following week she was very excited to tell me that she chose a conch shell that she had placed on her mantle years ago. She told me it was one of her favorite objects, BUT - she had never really “seen it” before she spent time drawing that shell.

So you see, drawing from observation slows us down, forces us to notice things and pay attention in a personal and intimate fashion. For any painter who works in a representationally, that engagement is certainly worthwhile.

Is drawing just for representational painters or does it have a place in non-representational painters as well? How so?

The short answer is, it depends on the artist and where their intention lies in their work.

As for myself, having had an extensive formal education and training in the art of drawing, I can testify that it has proven to be not only beneficial, but crucial to my abstract work for many years now. One might ask how, and why?

Part of the answer lies in my previous remarks regarding the act of seeing, carefully - and how vision supplies the imagination with countless moments of ideas and inspiration.

Then there are the formal issues surrounding the act of drawing, from compositional design to representing spatial play, light and shadow, form and volume, etc. This fact is borne out by the many abstract painters of the 20th and 21st century whose work and trajectory had their roots in drawing.

How does drawing fit into your larger practice as an artist?

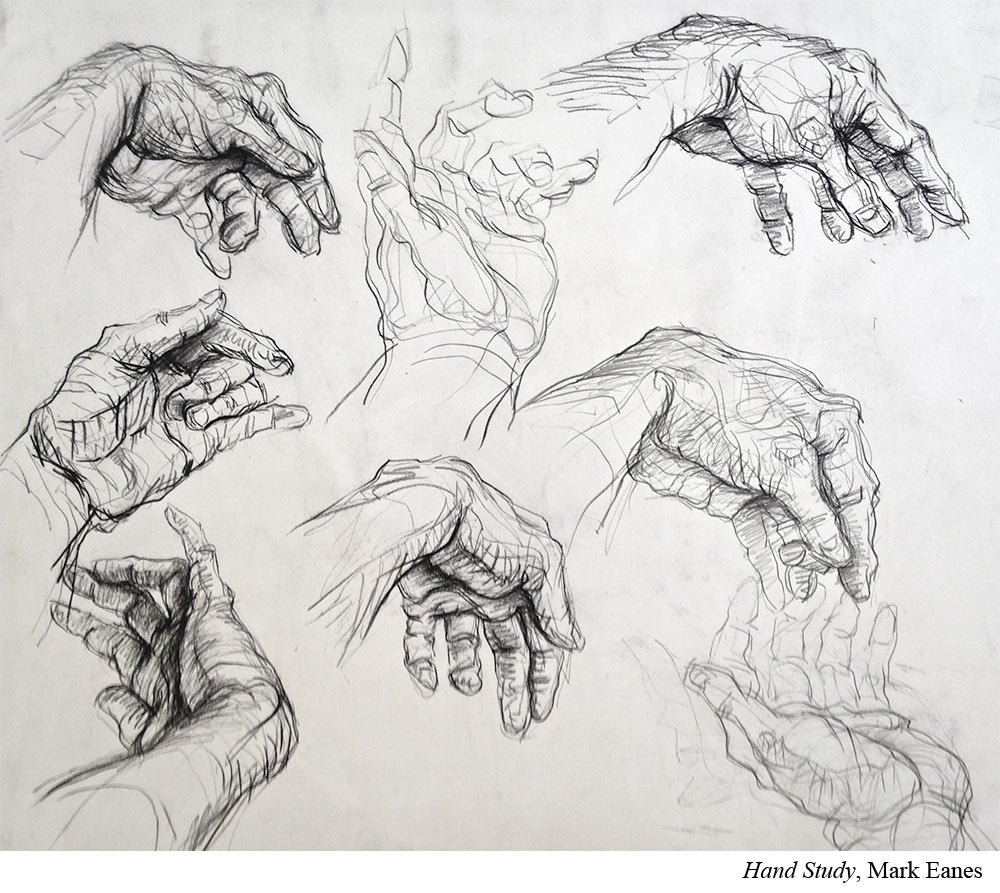

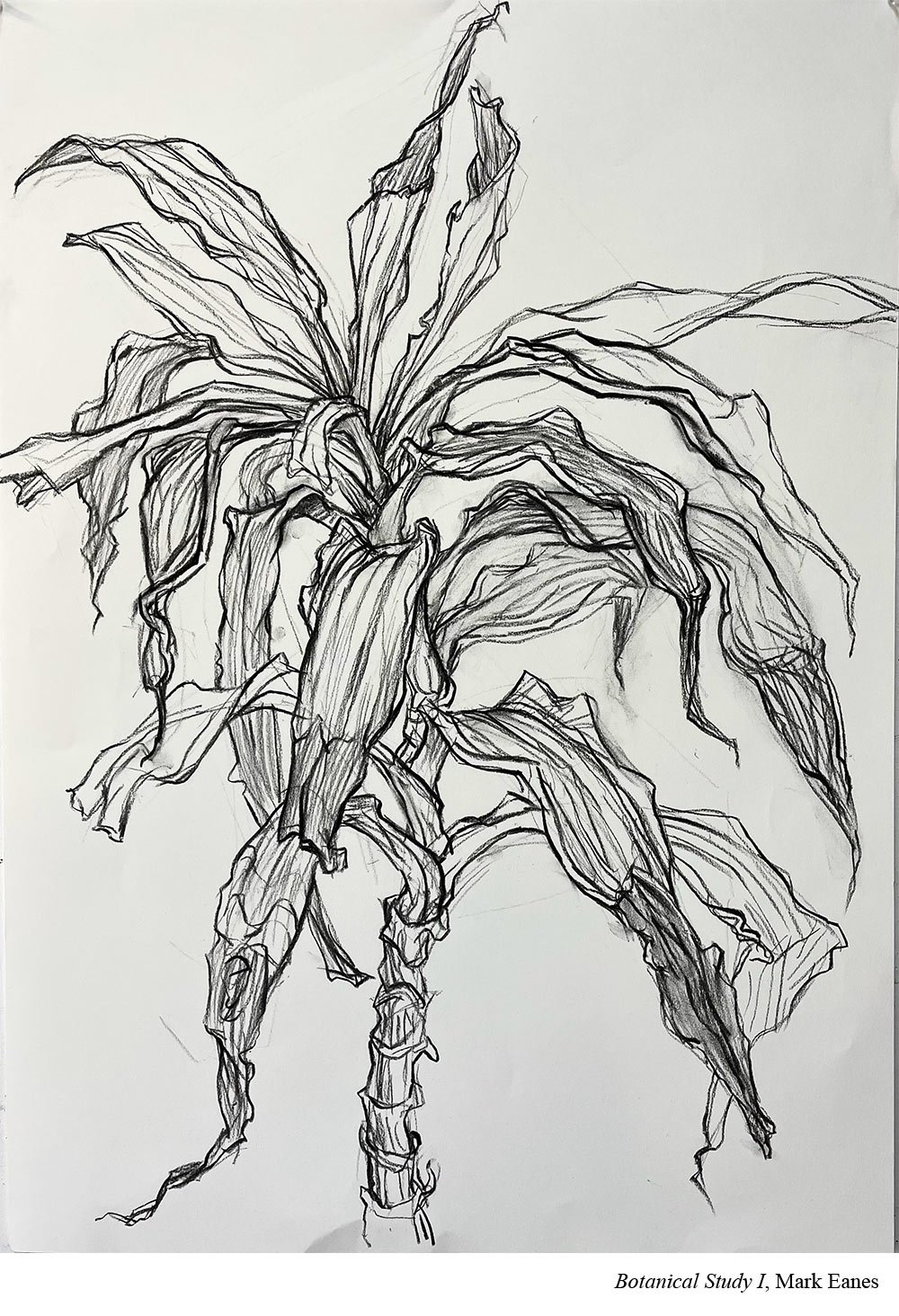

I continue to draw from observation (primarily the figure and botanical forms) for sheer pleasure and the challenge it provides. For many years I taught anatomy for artists at the California College of the Arts (CCA) and am humbled by how much I still do not know about the human figure. I find it endlessly compelling and rewarding…truly a lifetime project.

The same is true of botanical forms. For years I supported myself as a landscape gardener and have always had an interest in Nature’s miraculous designs. I used to paint from observation early on, but once I began to work in a non-representational mode, I kept the two practices separate. I enjoy how each discipline challenges me to solve problems in unique and specific ways.

What has the ability to draw given you as an artist? How have you seen it help your students?

Drawing has given me the gift of inquisitiveness. It has provided me with the ability to look at things with wonder and curiosity, to engage my imagination and at times to be in awe of what I am seeing and experiencing.

The writer Raymond Carver put it this way, “Writers don’t need tricks or gimmicks or even necessarily need to be the smartest fellow on the block. At the risk of appearing foolish, a writer sometimes needs to be able to just stand and gape at this or that thing — a sunset or an old shoe — in absolute and simple amazement.”

Drawing has given me that unique gift, to just stand and gape at this thing, or that thing.

As for my students, I would like to believe the same is true for some of them, but not all. Once again, it hinges on the person and what they wish to do, and say, in their work. That said, I do enjoy watching my students at CCA during studio hours. They are completely immersed, very focused — and in this age of distraction and shrunken attention spans, I am heartened to be a witness to their total engagement, not to mention the pride they feel when they pull off a strong drawing. It’s a beautiful thing to be a part of.

Fortunately many of my students have gone on to have very successful careers in art, either as an exhibiting artist, or some variation, as well as teaching. I hear from them from time to time and it’s gratifying when they stay in touch and thank me for my contribution to their journey.

Drawing can often feel frustrating. Why is that and any advice for a mindset shift that might help those frustrated with their drawing skills?

This is a very important question Kelly.

Not only is drawing frustrating for many folks, but they are intimidated and even fearful of learning how to draw. Mostly they are afraid of coming up short, fearful of failure.

Let me begin with this quote by Kimon Nicolaides, the author of the classic book, “The Natural Way to Draw”:

“The job of the teacher, as I see it, is to teach students, not how to draw, but how to learn to draw. They must discover something of the true nature of artistic creation - of the hidden processes by which inspiration works.”

Let me add to this - Drawing is a discipline, like all of the arts - music, dance, literature, etc. It is a skill set that can be learned by the absolute beginner. The most important factor here is desire. This is my first and most important message. True desire will carry the day. Always.

Without desire the student will not be able to practice what I call the three P’’s:

Practice

Patience

Perseverance

I often speak of the analogy of learning a musical instrument, say the piano for instance. That is quite an endeavor that will require a real commitment. One learns the piano by finding a good teacher and doing the work.

First, the scales, then in time, simple tunes. After months of practice the student advances to more challenging music and eventually begins to not only to read the notes, but feel the music.

“Drawing is a discipline, like all of the arts - music, dance, literature, etc. It is a skill set that can be learned by the absolute beginner.“

-Mark Eanes

Drawing is no different. My Language of Drawing course is designed and dedicated to those people who have a strong desire to draw, and I am confident if they can commit themselves to doing the work, they will succeed.

Finally this…just as a student of the piano must hit many, many wrong notes, so too the artist will make many poor drawings as part of the process. But with practice, patience, and perseverance the artist will hit the right marks and begin to understand that drawings are mere bi-products of their experience in seeing things more clearly, and find the means for expressing that way of seeing.

Does all drawing have the same purpose or are there different types of drawing?

What the artist has to say and express through drawing is a very personal matter. I encourage experimentation, to cut loose, to take risks and go into uncharted territory, to find ways to explore variations on a theme, in other words - to find their own creative voice, what some refer to as style.

In doing so, the artist begins to understand that drawing has many forms and purposes. Frank Gehry, the architect uses quick gesture drawings to conceptualize his remarkable buildings. Some like the quick sketch and take a sketch book with them as a personal visual diary, others like to spend hours on one drawing which allows them to have a deep dive into seeing what is before them. Others use drawing as a preparatory study for paintings, tapestries, sculpture, etc., while others may move into pure abstraction (think Mondrian’s remarkable journey from representational to non-representational).

At the end of the day, drawing is a powerful tool for not only seeing, but for imagining what is possible in the creative act of doing.

8) We think of learning to draw as an end goal (being able to render something accurately) but what is LEARNING to draw (the practice and act of practice) teach you as an artist?

I touched on this earlier but will endeavor to elaborate here.

First, let’s address this idea of “”learning to render something accurately.”

That is a loaded subject and goal. I can put a botanical subject in front of a dozen artists, and they each will render the subject differently. One might create a photo realist version while others’ drawings may look like the German expressionists.

One might ask, “Is one more real than the others?” All twelve drawings attempt to reproduce what is before them, but what I believe is more important is how each artist chooses (within their skill set) to interpret the subject. Reproduction versus Interpretation. This is a hard sell, but an important distinction. I’m in the camp that believes that each artist must decide for themselves what their intentions are, and how best to achieve those goals.

So what does drawing teach the artist? It teaches them to learn about their personal journey, their strengths and weaknesses, their means of expression, what they wish to say and how to say it.

One of my mentors once told me “The drawings never lie.”

When I asked her what she meant, she explained that unlike painting, a process that can have many hidden layers of adjustments and corrections, drawing tends to be very immediate. The paper does not forget. Our marks are there for the artist to see, for better or worse, and the drawing becomes a sort of barometer of our intentions, our imagination, our moments of clarity and uncertainty.

As Agnes Martin said, “ We can see perfectly but we cannot do perfectly. That is why Art is so very hard.”

If someone has limited time but is committed to getting better at painting long term, do you suggest they spend that time drawing or painting? Why? Any specific exercises you’d suggest?

Throughout my entire career as an instructor of painting , I have worked diligently to make clear the following concept to my students:

Learn to draw like you paint, and to paint like you draw.

My students have been able to achieve this dictum by practicing the many exercises I put before them.

For example, we work a great deal with charcoal tools which have the ability to draw in a painterly fashion, that is to say, focusing on tonal value, shifting edges, figure and ground relationships, etc. Charcoal can be pushed around, erased— the drawing taken back to a ghost image and then re-drawn and re-considered, much like painting.

Then, when they pick up their brushes to begin a painting, I will remind them to “draw with your brushes and treat them no differently from your drawing tools.”

And when it comes to color determination, I will remind them to “see color for its values, and explore what’s possible.”

They can do that because of all the tonal drawings they have achieved. Even line quality from chalk to brush is possible.

When I offer challenging subject matter (drapery, crumpled paper bags, the figure), I will have students create preparatory drawings (both sketches and long studies) to familiarize themselves with the subject and explore compositional and value studies.

You can learn more about Mark Eanes including his new course The Language of Drawing at MarkEanesAcademy.com. Use coupon code LEARNTOPAINT15 at checkout for a 15% discount on all Academy courses through May 15th.